You are essentially a start up of you, your very own CEO. How can you work in ways that give you a competitive advantage in the market of people-start-ups?

Lately, I have been thinking about work and what ways to work may be best suited for people who want to stand out. There are many excellent research books on optimising work processes, and I offer no attempt to compete with those in this reflection. Instead, I will talk about how to work as seen from the perspective of my experiences.

Throughout this reflection, when I speak of stress, I am referring to a combination of the number of things one has to do, the performance required on the tasks, and how critical those tasks are in terms of probably setting one apart.

On the other hand, work refers to the degree to which we voluntarily respond to stress demands. I, therefore, make the distinction between stress and work by thinking of stress as an external stimulus and work as a voluntary response to the same.

Quite often, we increase the amount of work we do as the stress increases. At this point, you are probably thinking of a robust linear correlation, as represented in the graph below.

The problem is that over any given timeframe, think a semester, quarter or year, the amount of stress is better modelled as a sinusoid. There are those periods when we are under enormous stress and those when it is fair to say that the stress is so tiny that relaxation is the path of least resistance, more like something in the graph below.

Of course, some people defy all expectations and never respond to stress of any sort; they never do anything. Given, I suppose, that you are still reading this article, you are most likely not one of those. However, if you are like most people, your stress response is captured in the graph below; you work harder when subjected to more stress and predictably work less when the stress is gone.

This is a perfectly normal way to work. However, I wonder if anyone can set themselves apart purely by working in this manner. To use an analogy of the stock market, one cannot beat the stock market to the extent that they consistently predict the market to move in the direction that every other analyst predicts. To beat the market, there must be some asymmetry between one’s predictions and the wisdom of the crowd. The same applies to our work and setting ourselves apart; to stand out, one must do many things others are unwilling or unable to do at some point. In fact, that follows from the very implications of what standing out will mean if taken literally.

Quite often, this is captured in advice that says we should work harder and “outwork the competition”. I think, however, that how hard one works is as important as when one works in response to the amount of stress. Given we cannot always outwork everyone (unless you are superhuman, that is a perfect recipe for burnout), our response to the stress cannot be to amplify our work curve as depicted in the graph below.

If you try this, I guarantee you will burn out and crash relatively quicker than you imagine.

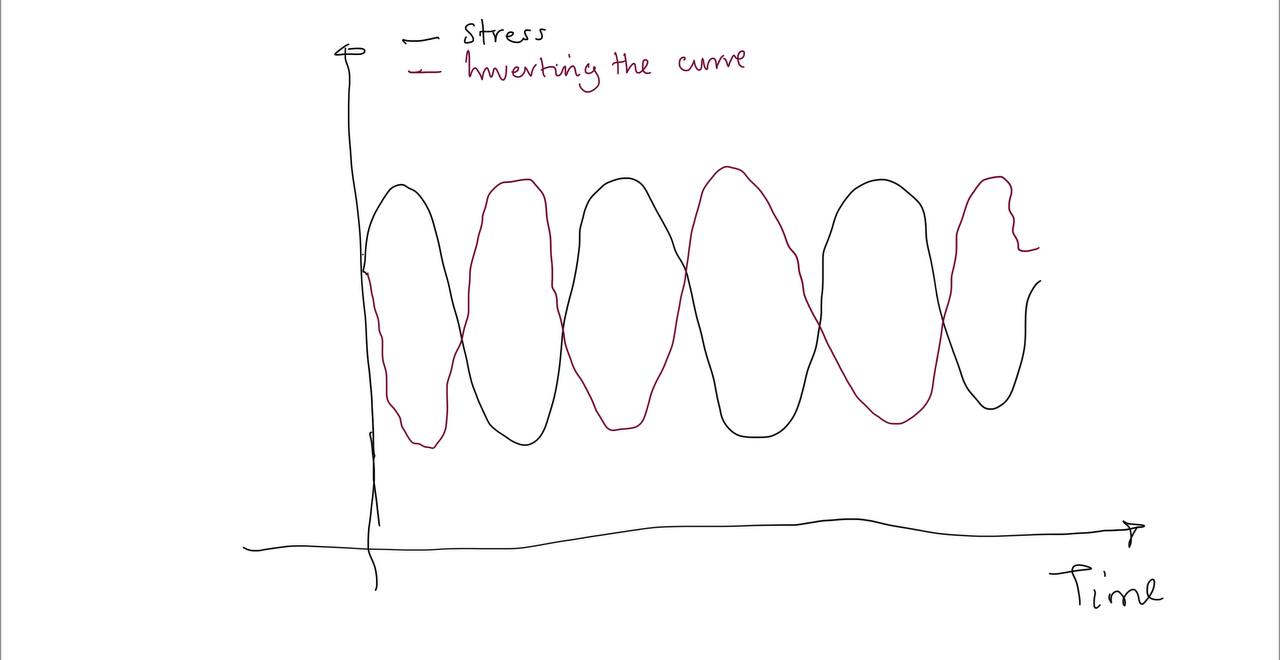

How, then, must we respond to stress in order to stand out? For the past years, my answer to this question has been something I refer to as inverting the curve. Simply put, work harder when it makes less sense to work hard, and then work less when it makes less sense to work less, almost like something you see in the graph below.

But lately, I have been wondering if this is optimal and trying to find ways to improve my approach to work. If all you do is invert the stress curve, so to speak, you will end up delivering spectacularly when the occasion demands, but I doubt that you will stand out. You could stand out, but it will only be to the extent that others fail to work as hard as the occasion demands.

To me, the advantages of inverting the curve have been the ability to think better under pressure (since, technically speaking, my work habits mean that I am under less stress than others around me) and to have the added advantage of being able to approach very tense situations from a distance and thus reduce the potential for wrong judgement.

I recently incorporated into my “inverting the curve” system the concepts of consistency, compound effect and holding oneself to higher standards. It makes for a more efficient approach to work that is likelier to help one stand out.

Of course, one still has to work longer hours and do more demanding things; there is no magic pill. But the question of when to do that work is the rate-determining step.

I now think as follows.

To stand out, you need to be doing more work when it makes less sense to work, and then when it makes more sense to work, you need to work slightly more than the situation demands. For example, when the system stresses everyone around you, you raise the stakes for yourself. If 90% is the optimal performance that the system demands of every participant, raise yours to 97%! Raise the stakes exactly when it is most expensive for others who have yet to be inverting the curve to raise the stakes as well.

The only reason you will be able to do this is that you have been inverting the curve, and the moat of experience and knowledge that you have consistently built over time will give you the advantage of raising the stakes without having to work a crazy amount of hours at any instant.

My current optimal response to stress is now captured in the graph below.

It is often said that a team is only as strong as its weakest link, and this “Inverting the curve 2.0” system seeks to exploit something along those lines. Simply put, if it is more expensive to stand out, you want to make it even more expensive and then stand out by leveraging the fact that you have consistently built an extensive war chest in happier times. And at that particular moment, when standing out is particularly crucial and expensive, it costs you way less in terms of the necessary work to stand out. Do not just invert the curve; raise the bar!

If you have read this far, I am delighted that I did not have to start by convincing you that hard work and being exceptional are essential; you are, quite clearly, already convinced about those. And so I will only reinforce that conviction.

Two things, in particular, are changing the job market; technology and globalisation. Technology will eventually replace mediocrity by offering cheap alternatives, but at the same time, it will render superstars more valuable. It will either make you a farmer or a god, and how that turns out is, probabilistically speaking, up to you. Globalisation, on the other hand, will render your status as a local champion useless. My prediction (maybe it is not very much mine as it is an observation of what is already obvious) is that standards will be global. While you celebrate that you can now get a remote job in the US and earn more, an 18-year-old kid in India is more likely to take that job away from you than you may imagine. I doubt that there has ever been a period in human history so rife with opportunity, yet I also doubt that there has ever been a time in human history so rife with competition.

I hope, of course, that you do not share this with anyone. If you do, and everyone around you starts practising it, then it makes it even harder for you to stand out by practising it. You get the joke, I hope!

Back to top