TL;DR

Knowing when to consolidate progress instead of constantly pushing for more growth is an art, and developing a sense of balance requires thoughtful resource allocation. Over-optimization can be counterproductive, and perfectionism can sometimes lead to wasted effort.

“Growth, we know all too well, is not a strategy. It is a tactic. And when undisciplined growth became a strategy, we lost our way.” ~ Howard Schultz in Onward.

In “Optimizing for the wrong metrics”, I argued that even though the natural consequence of having goals was setting, and then optimizing for certain metrics, the accurate definition of the metrics in question was a critical aspect of doing things that matter. I tried to convince you that if you merely adopted consensus metrics without a critical examination of how aligned they are with your goals, you will repeatedly hit your metrics but hardly realize the outcomes that are important to you.

Since then, my mind has wandered fruitfully around the idea of optimization.

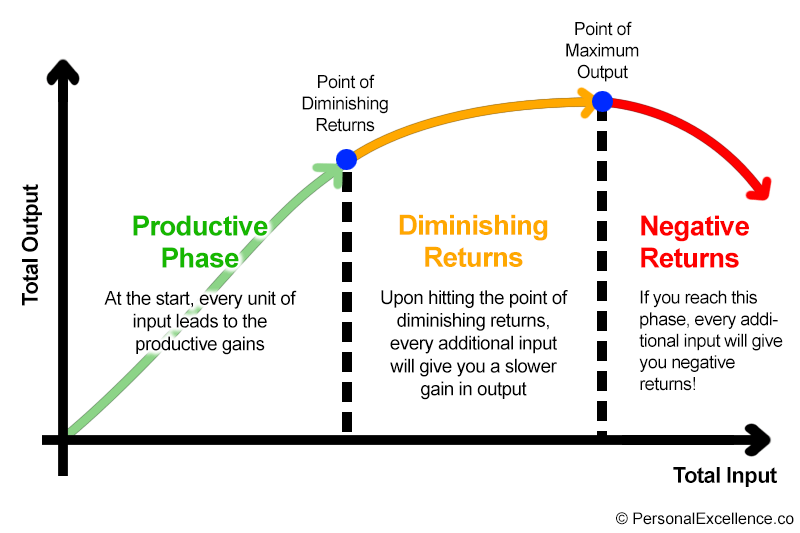

My inspiration came primarily from a painful observation I made as an undergraduate student. Towards the end of time in college, I observed that the relationship between effort and reward in terms of grades was diminishing in nature. It became obvious to me at some point that if one scored 70% on a term paper, it was often the case that by making minor adjustments such as paying more attention to grammar and organization, a significant improvement could be achieved; it was easy to move from a 70% to an 80%. In contrast, it took considerably more effort to move from 80% to 90%, and the chasm between 90% and a perfect score was so wide that to cross it would often require a complete rethinking of the key concepts presented in the paper.

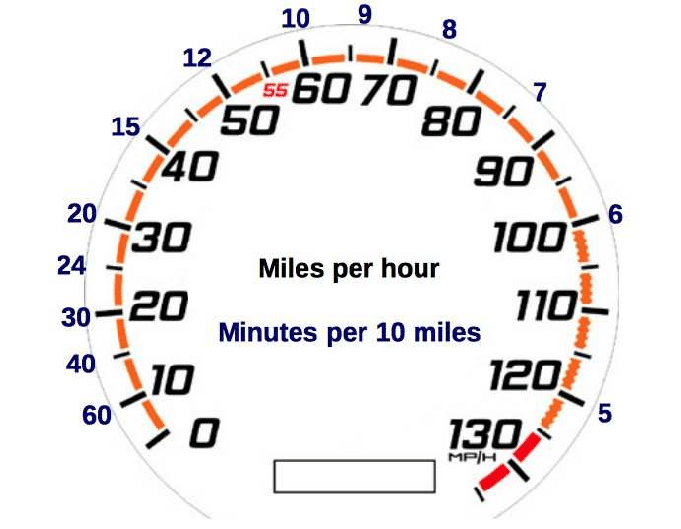

This is not an entirely new observation. Business people know all too well that very rapid revenue growth patterns are only a harbinger of the imminent challenge first of sustaining the realized growth, and then of harboring any dreams of further growth. And if your car has a speedometer showing values of pace (minutes per 10 miles) at selected levels of speed (mph), which is sometimes known as a paceometer, you may notice that while accelerating from a speed of 10 mph to 30 mph will save you 40 minutes in the time required to cover 10 miles, accelerating from 40 mph to 60 mph will save you only 5 minutes! And what is more? Driving at 60 mph can be considerably more dangerous than driving at 40 mph.

What are the implications of this observation with the three-part system - setting goals, picking metrics, and optimizing for those metrics - that many of us use unconsciously?

In very simple terms (borrowed from the Computer Scientist Donald Knuth): “Premature optimization is the root of all evil.”

Once you have picked the right metrics, it is important to: one, learn - either by close observation of the situation, or from the experiences of others - what sort of relationship exists between effort (in terms of time and resources) and the expected gains; two, determine at what point you have to prioritize consolidating your progress over growing at the levels previously experienced, or in other words, determine at what point you will be better off not being focused on growing.

The need for such a process is strengthened by the fact that unfortunately for us, our most precious resources and raw materials for realizing our goals, time and attention, are finite and the proper allocation of these resources is just as important (if not more important) than the other important factors such as hard work, dedication, and luck that are widely accepted as necessary conditions for success. We are resource allocators; it will be very costly to not have a framework that helps us appreciate the situations in which more can be less.

Is there a science for determining at what point more is less?

It seems more appropriate to argue that it is an art. Consider, to start with, that quite often, when one is performing this balancing masterly, even their best explanation for their system seems too simple to be true, and is often a post hoc justification. We seem to know we are doing it well, but cannot say very accurately how or why, and it only gets worse when we have a large number of diverse goals. Consider, also, that while there are a host of “scientific” decision-making frameworks that could be useful when making difficult decisions such as the pareto principle (80/20 rule), or marginal analysis, the failure of each of these frameworks to provide a silver bullet means that oftentimes the task of picking the most appropriate framework or combinations of the same is a subjective act that is closer to alchemy than magic. In “Good Taste” I argued that to succeed in life, one needed to have good taste. Good taste is also crucial as a defense mechanism for over optimization at uncontemplated costs; somehow, you just have to know what it is you should be working on at a given time, and when enough is enough.

It falls on each one of us to develop a good sense of taste (or aesthetics as my friend Jean thinks of it); no one can tell us how to do it and we just have to wander till we know when enough is enough, and when our balancing act is balanced. It is the case, however, that in trying to develop this taste that helps our balanced act, asking questions is more important than finding answers; it seems as though the wrong choices or decisions will avail themselves in a more prominent manner than the better options, and in thinking hard about how we optimize for our goals we may be less wrong, but never fully correct.

Perfectionists are particularly prone to this sin of uncontemplated optimization, and aphorisms that drive them to a crusade-like defense of this vice are rife in our culture. You must have heard that “how you do anything is how you do anything”, and that you should “do or do not, for there is no try”. The good news is that even God does not favor perfectionists, and has not given them an infinite amount of time and attention, and as members of a society that imposes constraints on what one can opt out of, at some point they learn (as I did), that it is okay to attend some meetings and daydream throughout, and that you need to, as a matter of urgency, pull an allnighter preparing for some: the trick is to know when.