TL;DR

Wild success requires two things: competence and ownership of upside. Being good at something isn’t enough—you must also capture the value created from your skills. This often depends on both personality and external trends (e.g., dot-com boom). While owning upside may seem innate to some (like salespeople or performance-based CEOs), it can also be learned and improved by aligning self-knowledge with opportunities. There’s no universal formula, but the key is to keep asking: how can I keep getting better, and how can I own more of my upside?

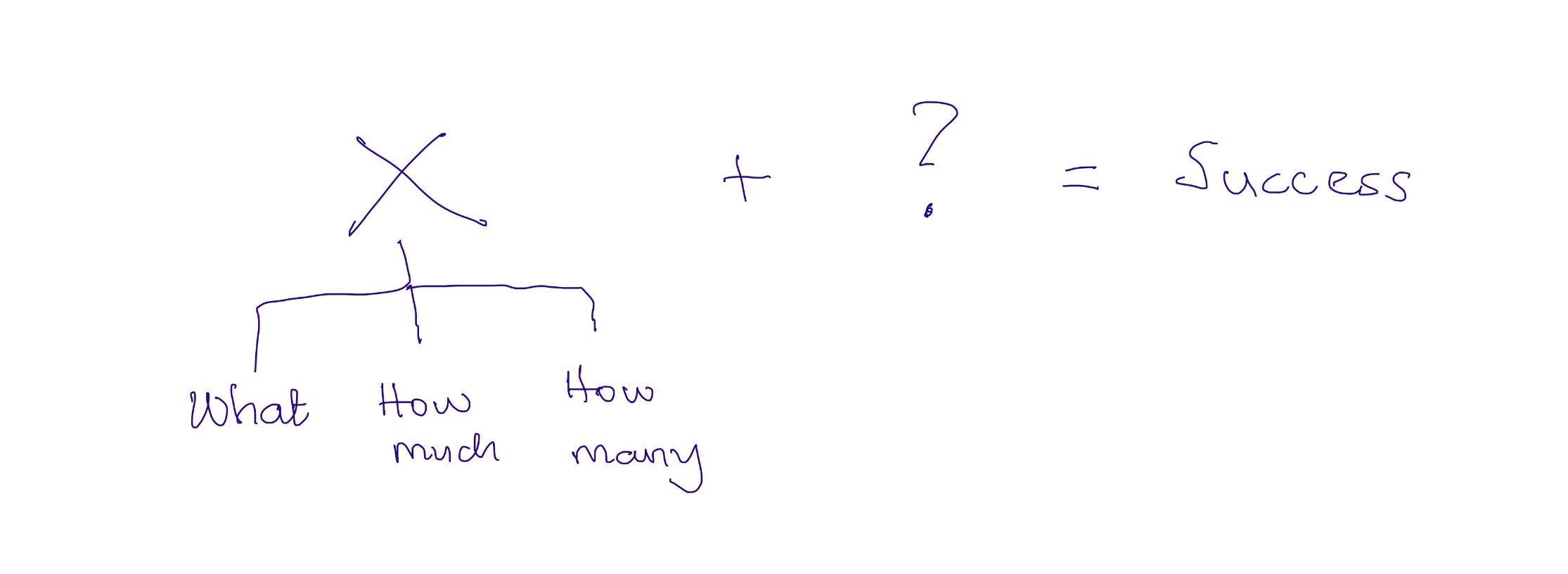

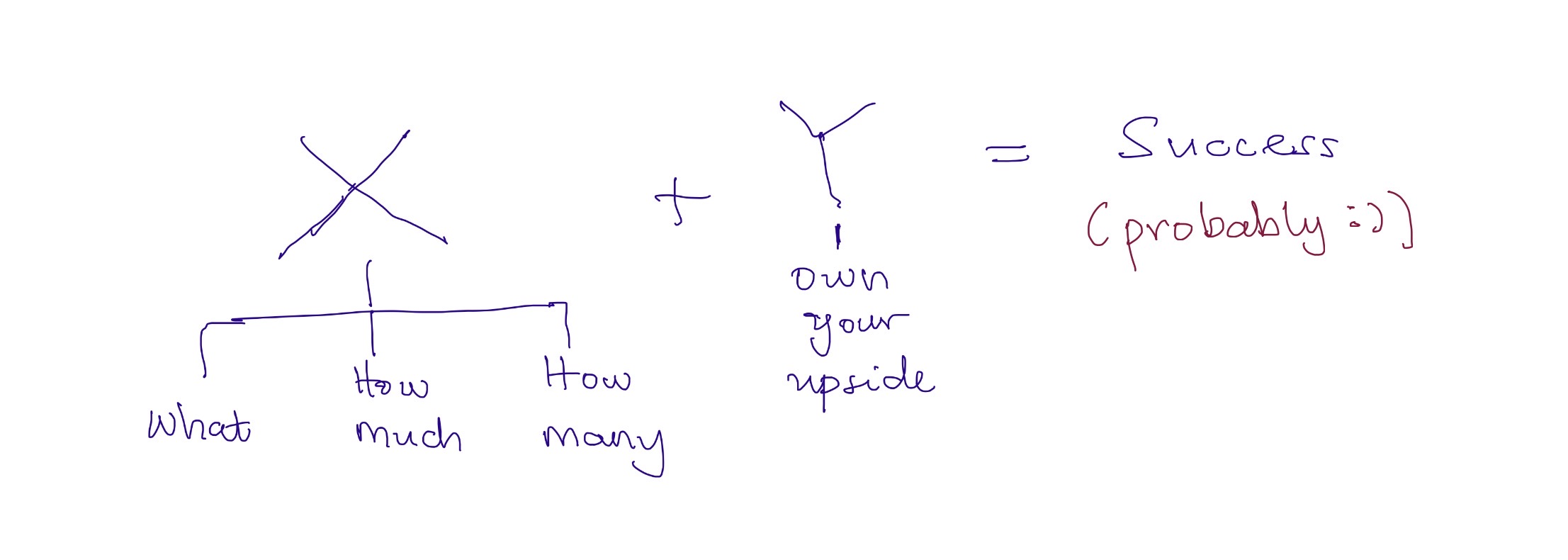

Most advice about what it takes to be wildly successful often emphasizes the need to be good at something. Although most people agree with the essence of that message, particularities emerge concerning 1) what it is that one should desire to be good at, 2) the number of things at which one can/should reasonably hope to be good at, and 3) the desirable amount of depth.

The summation of these ideas seems to me to be only one variable of the “wild” success equation.

There is regrettably very little advice about the role owning one’s upside plays in enabling wild success. Understandably so; anyone who has given good thought to the subject will quickly concede that it is more art than science. A corollary of owning one’s upside is that luck plays a huge role in enabling success (it is a corollary when one considers that for luck to enable success the upside will have to be owned by the subject). While this is increasingly being acknowledged, there is still a gap in the public discourse on the matter of how one can leverage (I used the word leverage here in the investment-banking sense) their being good to achieve wild success without waiting on “outlier luck.”

My insight in this regard is that to be wildly successful, in addition to being good at something, one must own their upside: one must continuously seek to create situations in which they can capture as much of the value as they create from being good at something.

I am very tempted to say, as many have on the question of what makes a good leader, that people who master the art of owning their upside are born and not made. Consider, for example, that two of the careers in which we find the most wildly successful people in society and for which the private ownership of upside is almost a given are very reliant on innate capabilities that are hard to emulate. Consider the commission-based salesman and the high-flying CEO who negotiates only performance-based compensation; you can hardly convince someone to change how attractive they find such arrangements, and most people have already made up their minds on the question before they give it proper thought.

However, a good case can be made about the fact that sometimes societal trends can conspire to modify the population’s proclivities towards owning their upside. Consider, for example, that the dot-com bubble made prominent three types of value-extractors: the dreamers who gave everything towards starting and owning companies; the moderate-but-yet-smarts who found arrangements by which they could get huge salaries AND share in the ownership through what were largely performance/value-based stock vesting agreements; and the cautious who opted for salaries. While I had no first-hand experience of the boom, I am confident that it wouldn’t be smooth to attempt fitting people from these three categories into the previously mentioned two. There are external factors that supplement internal factors in enabling us to better own our upside.

Perhaps it is not all personality-based, and can be learned. I am not sure. I am sure, however, that all of us can benefit a little bit more from exploring ways in which we can leverage an exact understanding of ourselves and our situations to improve our ability to own our upside. If you are already thinking about and trying to get good at anything, you are leaving value on the table if you do not ALSO think about how you can increasingly own more of your upside.

Given, as I already pointed out, my suspicion that this is more art than science, you may agree with me that it is almost impossible to lay out a universal AND accurate plan for how to own one’s upside. What is not impossible in the pursuit of wild success, I think, is to continuously ask 1) how one can keep getting good (what, how much, how many) and 2) how one can increasingly own their upside (especially to the extent that it deviates from the normal). And I think it is more important in this case to have questions than answers. The answers change: the questions hardly so.

While acknowledging the gross reductionism that some may accuse me of, I hope that I have convinced you that it is not enough to just be good, and that your mental model of what it takes to be wildly successful looks now like the equation below: mastery AND upside.

NB.

A trusted reviewer pointed out that I did not suggest what it is that one must do with their downside. In response, I will mention in brief that one must outsource their downside. Any downside that one commits to getting good at should no longer be considered a downside as the goal is now to be good at it (and I hope seriously so). Whatsoever downside remains a downside must be outsourced (that is exactly what you do when you buy an insurance premium and what MBA types are doing when you find them looking for “technical co-founders”).

A second comment that was well received was that it would have been good to explore in more depth how to model a journey of learning to own upside. In response, I commit to writing a sequel with the prescribed focus.