TL;DR

The essay explores the dangers of overestimating what we know and falling for the illusion of knowledge in a world saturated with information. It advocates for: 1. Honesty about the limits of our understanding. 2. Courage to admit ignorance and resist pretending expertise. 3. Disciplined curiosity through relentless questioning (why, what, how) to deepen understanding. 4. Treating knowledge as a growing conversation rather than dogma. It critiques shallow shortcuts to mastery, highlights the pitfalls of abstractions, and questions betting as a truth-seeking mechanism. Ultimately, it calls for a balance of intellectual humility and rigor in navigating today’s complex knowledge landscape

“It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.“ [It is not what you know that saves you, it is knowing where what you know ends] – Mark Twain.

Do you know what you do not know? Better still, are you courageous enough to admit that you do not know the things that you do not know?

We live in a world in which a lot of knowledge is abstracted; every corner of the internet has someone selling you material that is supposed to lead you to mastery of XYZ in 24 hours. In their defense, these people are selling a product for which there is genuine demand. There is too much to know, and apparently not enough time for knowing.

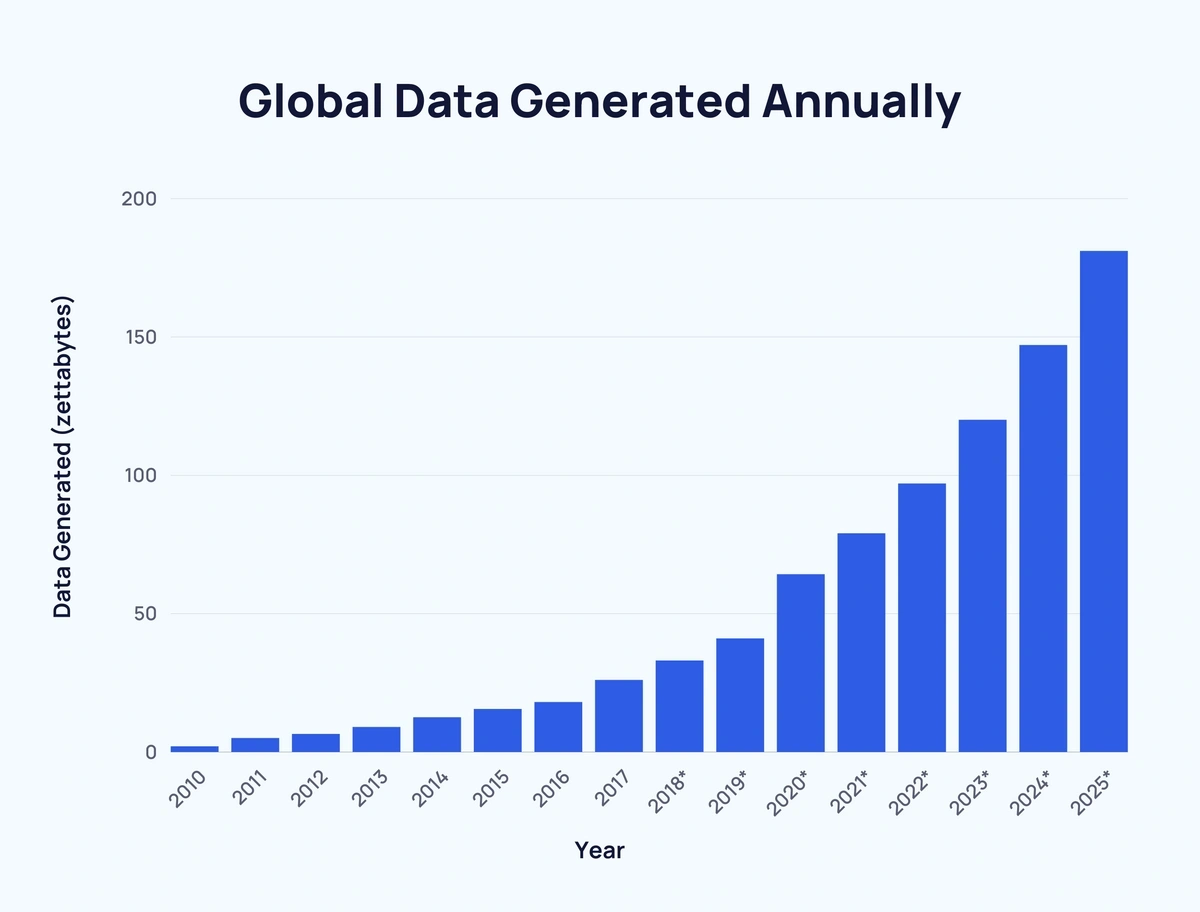

According to Statistica, in the 13 years between 2010 and 2023, the volume of data/information created, captured, copied and consumed worldwide has increased by 74-fold. In the last two years, we have created almost 90% of the world’s data. If we were to use the volume of data as a proxy for knowledge, the amount of 1) useless knowledge that we must cut out, and 2) amount of useful knowledge that must be consumed to know just about anything is mind boggling. That there is much demand for easy mastery is understandable.

The demand for easy mastery in itself is not a net negative in the same way that a difficult path to mastery is not inherently a net positive. If we can find easy and efficient paths to mastery we can significantly increase our creative power; that will be a net positive. The emphasis on efficiency is important because in the business of learning, inefficient approaches are easy, and the quest for easy and efficient approaches is itself herculean. The most significant problem with the demand for easy ways to mastery is that it creates an illusion of knowledge that presents itself without shame and with courage in buzzwords.

A good way to think about the consequence of illusionary knowledge is to say that we build non-trivial abstractions. I qualify them as non-trivial because quite often they manifest themselves by increasing our vocabulary without making it immediately obvious that we have not fully grasped the concept/phenomenon that newly acquired words seek to capture. My favorite culprit for this is the word innovation. If you ever go to business school and listen to case discussions, you may quickly realize that just about anyone can sound knowledgeable by using the word innovation frequently. If you are knowledgeable enough about the case, you can treat yourself to prime entertainment by just pushing people further with why and how questions.

The problem with abstractions is accurately captured in Joel Spolsky’s Law of Leaky Abstractions: “All non-trivial abstractions, to some degree, are leaky.” Spolsky’s law, being inspired by the observation of software systems that have a reputation for being fairly exact, is in my opinion, very generous. An adaptation for the abstractions that are rampant in our conceptual understanding of phenomena would arguably be less forgiving, as all non-trivial abstractions are very likely to be leaky. That is why we try to cut abstractions, and tell ourselves that if we can’t teach a concept to a child then we do not really understand it.

How many things can you teach to a child? That may be just about the number of things that you know.

The proper reaction to this phenomenon is to be diligent in mastering the things we know, and to be ruthlessly honest about the things we do not know; to realize that the critical step of efficient application of knowledge is not in its hoarding but in the accurate demarcation of what we know and what we do not know, and the courage to not cross that boundary. Two values are important here; honesty, and courage.

These are not entirely new values, and even Shakespeare and Dostoyevsky had alluded to them. In Shakespeare’s Prince Hamlet, Polonius advice to his son Leartes on how he must behave whilst at university is: “This above all: to thine own self be true, And it must follow, as the night the day, Thou canst not then be false to any man.” Dostoyevsky, who was influenced by Shakespeare, expands on this: “Above all, don’t lie to yourself. The man who lies to himself and listens to his own lie comes to a point that he cannot distinguish the truth within him, or around him, and so loses all respect for himself and for others”.

Even if one were to be honest about what they don’t know and courageous enough to fight the urge to appear knowledgeable about things about which they are ignorant, they will inevitably interact with many people who do not operate by the same principles.

How should one approach these interactions?

I think there are two parts to a correct approach. Firstly, always ask why, when, where, what, and how; always ask till you understand it in your child’s brain. Until then, keep a modicum of doubt. Asking these questions with a clear end goal in mind will not only help you better understand the topic under consideration, it will serve as a yardstick to measure the knowledge of your interlocutor. Secondly, one must approach all knowledge as part of a growing conversation, not as dogma; one must realize that their view of international trade if they were taught by Paul Krugman will be very different from their view if they were taught by Milton Friedman. In this sense, every newly acquired bit of knowledge enables one to contribute skillfully to never ending discussions on the topic under consideration, but does not necessarily make one an expert on the topic.

It has become increasingly popular to think that another way to approach such interactions is to challenge people to bets. The thinking goes that if we force people to put their money where their mouths are (skin in the game), we will incentivize truth-seeking behavior. I disagree with this approach because 1) it assumes that the bets are risky, 2) the risk is equal for participants, and 2) that the people making them care about risk management. Consider for example, two persons, A and B, who cannot agree on what the capital of Australia is. A’s monthly salary is $500, and B’s monthly salary is $5000. To settle the dispute, A challenges B to a $100 bet. A has a greater incentive to be right as he stands to lose 20% of his monthly salary, while B may not pay attention because he stands to lose only 2% of his monthly salary. If there are multiple bets, one can imagine a point where B loses so much money that he starts to care. However, because it is also possible that B is a degenerate gambler whose risk management strategy is to observe the movement of the moon to inform his bets, we cannot expect his newly found concern for the bet to be of much value to our quest for the truth. When such a betting market grows to include people without discrimination, it becomes another type of stock market, producing signals that can sometimes be completely out of tune with the fundamentals. Bets are important, but not sufficient.

We live in a time where the illusion of knowledge is a pervasive challenge. The sheer volume of information, paired with the demand for rapid mastery, creates a fertile ground for abstraction-heavy, surface-level understanding. Perhaps there has never been a better time when knowing what one does not know is an advantage. To navigate this, it is important to cultivate honesty about our own limitations and embrace the courage to admit what we do not know. When engaging with others, the key is a disciplined curiosity. If done right, and in conjunction with challenges that force others to have “skin in the game”, we can prevent ourselves from being led into temptation by those who do not know what they do not know.

Honesty, courage, and disciplined curiosity; that is how we manage what we know and draw boundaries around what we think we know.